Milledgeville, Georgia

Milledgeville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Motto(s): "Capitols, Columns and Culture" | |

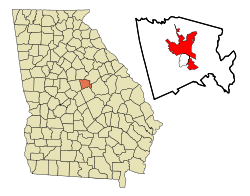

Location in Baldwin County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 33°5′16″N 83°14′0″W / 33.08778°N 83.23333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | |

| County | Baldwin |

| Incorporated | December 12, 1804 |

| Named after | John Milledge |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Mayor | Mary Parham-Copelan |

| • Manager | Hank Griffeth |

| • Council | Members

|

| Area | |

• Total | 20.42 sq mi (52.89 km2) |

| • Land | 20.26 sq mi (52.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.161 sq mi (0.416 km2) |

| Elevation | 330 ft (100 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 17,070 |

| • Density | 839.98/sq mi (324.31/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 31061 |

| Area code | 478 |

| FIPS code | 13-51492[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0332390[4] |

| Website | milledgevillega |

Milledgeville (/ˈmɪlɪdʒˌvɪl/) is a city in and the county seat of Baldwin County, Georgia, United States.[5] Founded in 1803 along the Oconee River, it served as the state capital of Georgia from 1804 to 1868, including during the American Civil War. The city's layout—modeled after the grid plans of Savannah, Georgia, and Washington, D.C.—reflects Milledgeville's intended role as a planned seat of government. During its years as the capital, Milledgeville quickly became a hub of political activity and cotton-based commerce before facing significant economic changes after the capital was relocated to Atlanta in 1868.

Today, Milledgeville lies along the Fall Line Freeway, a major east-west corridor that connects Milledgeville with historically significant cities like Augusta, Macon, and Columbus. Its historic core, including the Old State Capitol, is preserved within the Milledgeville Historic District in downtown Milledgeville.

Milledgeville is home to a public school district, private K-12 schools, and three colleges: Georgia College & State University, Georgia Military College, and Central Georgia Technical College. These institutions contribute to both the cultural and economic vitality of the city. Other key sectors include healthcare, retail trade, and public administration. Tourism also supports the local economy, with visitors drawn to features like the city's historic architecture, Lake Sinclair, and Andalusia, the former home of author Flannery O'Connor.

Milledgeville is the principal city of the Milledgeville micropolitan area, which had a population of 43,799 as of the 2020 United States census.[6] The city itself had a population of 17,070. In recent years, local leaders have prioritized economic diversification and downtown revitalization as part of broader efforts to support growth and attract investment.

History

[edit]Milledgeville served as Georgia’s state capital from 1804 to 1868 and played a central role in shaping the state’s early development.[7] Established during a period of territorial expansion following treaties with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the city became the state's center of political activity and remained so through the American Civil War, after which the capital was relocated to Atlanta.[8] In the decades that followed, Milledgeville responded to the challenges of losing its capital status by expanding public institutions and higher education and, more recently, by investing in economic diversification and downtown revitalization.[9][10]

Milledgeville, named for Georgia governor John Milledge (1802–1806), was established in 1804 as Georgia’s new centrally located capital.[7] Its founding followed the 1802 Treaty of Fort Wilkinson, through which the Muscogee (Creek) Nation ceded land west of the Oconee River to the state.[11] Prior to this, the area had been the subject of prolonged conflict between settlers and the Creek Nation, including violent clashes known as the Oconee War.[8] Planned as a grid-based city similar to Savannah, Georgia, and Washington, D.C., Milledgeville quickly rose in prominence, serving as Georgia's capital for over six decades until 1868.[12]

As Georgia’s capital, Milledgeville grew into a hub of political activity and cotton-based commerce in the decades leading up to the American Civil War.[12] The city's economic expansion was built in part on the labor of enslaved people, who worked on plantations and within the town as domestic workers, skilled tradespeople, and general laborers.[7] By 1828, nearly half of Milledgeville's 1,599 residents were enslaved; only 27 identified as free Black residents.[8]

Milledgeville continued to expand with the addition of major state institutions, including a penitentiary and the Georgia State Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum (now Central State Hospital).[13][12] Taverns, hotels, shops, banks, and newspapers also emerged during this period,[14][8] and in 1838, Oglethorpe University was founded as one of Georgia's earliest chartered colleges.[15] As Milledgeville developed, its appearance began to shift from a frontier town to a more established capital with larger, more refined buildings. Among these were a new statehouse (now known as the Old State Capitol) and an Executive Mansion (now referred to as the Old Governor's Mansion).[16][14]

By the late 1850s, tensions over slavery and states' rights culminated in political crisis. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, a secession convention was held on January 16, 1861, with approximately 300 voting delegates in attendance.[8] On January 19, the convention adopted the Ordinance of Secession by a vote of 208 to 80, making Georgia the fifth state to secede from the Union. Shortly afterward, Georgia joined South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana to form the Confederate States of America.[17] During the American Civil War, Milledgeville contributed troops and supplies to the Confederate cause, but the community endured several hardships including inflation, shortages, and one of several regional food riots.[18]

In November 1864, during the American Civil War campaign known as the March to the Sea, Union General William T. Sherman and 30,000 troops entered Milledgeville.[14] The campaign, which began in Atlanta and ended in Savannah, aimed to weaken the Confederacy by destroying infrastructure, supply lines, and civilian morale.[20] Although Milledgeville avoided widespread destruction, several military sites were damaged, grain and livestock were seized, and homes were looted.[12] After the war's conclusion in 1865, Milledgeville faced major economic disruption. Confederate currency became worthless, infrastructure was damaged, and many citizens bartered for basic goods amid widespread poverty.[9]

In 1868, the Georgia General Assembly moved the state capital to Atlanta, which was emerging as a transportation and commercial hub.[21] The relocation marked a significant shift in political and economic power, leading to a decline in population that slowed Milledgeville's recovery.[9] Recovery efforts during the Reconstruction era focused on restoring the asylum and penitentiary, while many farmers transitioned to the crop-lien system—a practice that often trapped them in cycles of debt.[9] In the following decades, the founding of Middle Georgia Military and Agricultural College (now Georgia Military College) on the former state capitol site in 1879,[22] and Georgia Normal and Industrial College (now Georgia College & State University) on the former penitentiary grounds in 1889, contributed to the city's revitalization.[23] The continued operation of the asylum—renamed Georgia State Sanitarium in 1897—alongside these institutions helped sustain Milledgeville’s recovery into the twentieth century.[12]

The early 20th century brought additional challenges and change. Milledgeville's agricultural economy was disrupted by the boll weevil infestation,[12] which devastated cotton crops across Georgia, pushing many farmers to diversify their crops or seek employment outside agriculture.[24] Central State Hospital, as the former asylum came to be known, grew into one of the largest mental health institutions in the United States,[12] housing over 12,000 patients by the 1960s.[25] While its scale and mission were once seen as progressive, the hospital also became the subject of criticism over time, particularly related to overcrowding, inadequate treatment, and patient mistreatment—issues that reflected broader shortcomings in institutional mental health care across the U.S.[25] The national movement toward deinstitutionalization and the rise of community-based mental health services later led to a steady decline in the hospital's operations and workforce.[26][27]

Economic diversification efforts gained momentum mid-century.[10] The creation of Lake Sinclair in 1953 by the Georgia Power Company spurred recreational tourism,[28] and subsequent historic preservation projects in the 1980s and 1990s revitalized downtown Milledgeville.[7] Recognition of the city's antebellum heritage, combined with community development initiatives like the Main Street Program,[29] boosted heritage tourism and strengthened Milledgeville's cultural identity.[7]

In the 21st century, local leaders have continued to diversify and strengthen Milledgeville's economy in response to the downsizing of Central State Hospital.[30][31] Combined with state budget cuts and the closure of several correctional facilities, these changes significantly impacted the availability of local jobs and economic stability.[10] As a result, the Milledgeville community has focused on attracting private investment, supporting small businesses, and expanding job opportunities in other sectors.[10]

Geography

[edit]Milledgeville is situated along the Atlantic Seaboard fall line, a geological boundary that marks the transition between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of the United States.[32] This location results in gently rolling terrain and a mix of soil types, including red clay common in the Piedmont region.[33] The city lies along the Fall Line Freeway, a major east–west transportation corridor that follows the fall line and connects Milledgeville to other historically significant cities in Georgia, including Columbus, Macon, and Augusta.[34]

Milledgeville has a total area of 20.42 sq mi (52.89 km2), of which 20.26 sq mi (52.47 km2) is land and 0.161 sq mi (0.416 km2), or 0.79%, is water.[35] The Oconee River flows just east of the downtown area and continues southward to merge with the Altamaha River, eventually reaching the Atlantic Ocean.[36] Just north of the city lies Lake Sinclair, a 15,300-acre reservoir created by damming the Oconee River in 1953.[28]

Climate

[edit]Milledgeville has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) with hot, humid summers and mild winters.[37] Average high temperatures peak in July, while January tends to be the coldest month. Rainfall is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year, with summer thunderstorms being common.[38] Snowfall is rare but does occasionally occur during the winter months.[39]

| Climate data for Milledgeville, Georgia, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1891–2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

86 (30) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

101 (38) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.1 (23.4) |

77.9 (25.5) |

84.3 (29.1) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.3 (34.1) |

98.9 (37.2) |

100.1 (37.8) |

100.0 (37.8) |

95.2 (35.1) |

88.6 (31.4) |

82.2 (27.9) |

75.5 (24.2) |

102.1 (38.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

59 (15) |

65 (18) |

74 (23) |

81 (27) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

81 (27) |

76 (24) |

64 (18) |

58 (14) |

74 (23) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 45.5 (7.5) |

49.0 (9.4) |

55.6 (13.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

71.0 (21.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

80.6 (27.0) |

75.1 (23.9) |

64.7 (18.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

48.1 (8.9) |

63.9 (17.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.0 (0.6) |

36.1 (2.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

48.8 (9.3) |

57.9 (14.4) |

66.8 (19.3) |

70.3 (21.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

63.9 (17.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

40.5 (4.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

51.4 (10.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.6 (−8.6) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.6 (6.4) |

56.0 (13.3) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.0 (16.1) |

48.9 (9.4) |

34.8 (1.6) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

13.3 (−10.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

53 (12) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

1 (−17) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.20 (107) |

4.40 (112) |

4.75 (121) |

3.90 (99) |

3.16 (80) |

4.30 (109) |

4.16 (106) |

4.73 (120) |

4.22 (107) |

2.83 (72) |

3.36 (85) |

4.49 (114) |

48.5 (1,232) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.3 (0.76) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.6 (1.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.4 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 7.9 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 9.5 | 108.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA[40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[41] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]As of the 2020 United States Census, Milledgeville had a population of 17,070, reflecting a slight decline from the 2010 population of 17,715.[6] The city's median age was 27.1,[6] lower than the state median of 37.4 years.[42] In terms of racial composition, 47.9% of residents identified as White (non-Hispanic), 45.3% as Black or African American (non-Hispanic), 1.6% as Asian (non-Hispanic), 0.2% as American Indian or Alaska Native (non-Hispanic), 0.1% as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic), 2.2% as some other race (non-Hispanic), and 2.7% as two or more races. Additionally, 3.3% of residents identified as Hispanic or Latino of any race.[43] The median household income in Milledgeville was approximately $39,669, which is below both the state and national averages, and the poverty rate stood at approximately 41.3%, significantly higher than the national average of 13.5%.[44]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,256 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,069 | 64.7% | |

| 1840 | 2,095 | — | |

| 1850 | 2,216 | 5.8% | |

| 1860 | 2,480 | 11.9% | |

| 1870 | 2,750 | 10.9% | |

| 1880 | 3,800 | 38.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,322 | −12.6% | |

| 1900 | 4,219 | 27.0% | |

| 1910 | 4,385 | 3.9% | |

| 1920 | 4,619 | 5.3% | |

| 1930 | 5,534 | 19.8% | |

| 1940 | 6,778 | 22.5% | |

| 1950 | 8,835 | 30.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,117 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,601 | 4.4% | |

| 1980 | 12,176 | 5.0% | |

| 1990 | 17,727 | 45.6% | |

| 2000 | 18,757 | 5.8% | |

| 2010 | 17,715 | −5.6% | |

| 2020 | 17,070 | −3.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[45] | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 8,176 | 47.92% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 7,728 | 45.28% |

| Two or More Races | 454 | 2.66% |

| Some Other Race (non-Hispanic) | 382 | 2.24% |

| Asian alone (non-Hispanic) | 280 | 1.64% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native (non-Hispanic) | 33 | 0.19% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 17 | 0.10% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 555 | 3.25% |

| Note: The U.S. Census Bureau considers Hispanic or Latino to be an ethnicity, not a race; individuals who identify as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.[46] All racial categories refer to respondents who reported only one race, unless otherwise noted. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. | ||

Economy

[edit]In recent decades, Milledgeville's economy has undergone significant changes as the community worked to offset the decline of employment at state-run facilities.[47] The downsizing of Central State Hospital, combined with state budget cuts and the closure of multiple correctional institutions, led to substantial job losses and economic challenges in the area.[31] The impact was further intensified in the late 2000s, when the city’s manufacturing sector contracted. In 2008, Rheem Manufacturing closed its Milledgeville operations, relocating production to Mexico and eliminating approximately 1,500 jobs.[47] Shortly afterward, Shaw Industries shut down its carpet yarn plant, resulting in an additional 150 job losses.[48]

In response to these shifts, local leaders have prioritized diversifying Milledgeville’s economy by attracting private investment, supporting small businesses, and expanding opportunities across a broader range of industries.[10] Efforts to recruit new industries and improve local infrastructure have included grant-supported improvements to the Smith-Sibley Industrial Park and initiatives focused on downtown revitalization.[49][50]

As of 2025, the leading sectors of Milledgeville’s economy by employment numbers include healthcare and social services, education, retail, and public administration.[51] Healthcare and social services account for the largest share of employment, with over 3,600 jobs across more than 200 establishments.[51] Education services, including Milledgeville’s colleges and schools, contribute approximately 2,100 jobs.[51] Retail trade and public administration also remain major employment sectors, with around 2,100 and 1,600 jobs respectively.[51]

Milledgeville’s higher education institutions and local tourism, in particular, contribute significantly to employment and commercial activity.[52][53] The presence of Georgia College & State University and Georgia Military College provides not only job opportunities but also drives local business activity through student spending, cultural events, and campus-related initiatives.[52] Tourism adds to the economic base as well, with visitors drawn to attractions such as the Milledgeville Historic District, Antebellum architecture, Flannery O'Connor's Andalusia Farm, and outdoor recreation at Lake Sinclair.[30][54] In 2016, tourism generated $88.7 million in direct spending in Baldwin County, supported 796 jobs, and contributed over $6 million in state and local tax revenue.[53]

Government

[edit]The Milledgeville City Council is the city's legislative body, responsible for passing ordinances and resolutions and overseeing the city's budget.[55] The council consists of six members, each elected to represent one of the city's districts, while the mayor is elected at-large for a four-year term.[55] Together, the mayor and council oversee public spaces, city infrastructure, nuisance regulation, public safety, and the management of street and sidewalk improvements, among other responsibilities.[56]

Mary Parham-Copelan, elected in 2017, serves as mayor.[57]

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]Milledgeville's public schools are operated by the Baldwin County School District, which includes multiple elementary, middle, and high schools, as well as early learning and early college programs.[58] As of the 2023–2024 school year, the district serves approximately 4,588 students with 348.90 full-time equivalent (FTE) classroom teachers, resulting in a student–teacher ratio of about 13.15:1.[59] The district includes four elementary schools (Lakeview Academy, Lakeview Primary, Midway Hills Academy, and Midway Hills Primary), one middle school (Oak Hill Middle School), one high school (Baldwin High School), the Early Learning Center (for Pre-K students), and Georgia College Early College (serving students in grades 6 through 12).[58]

Private schools

[edit]Private K–12 education is available through Georgia Military College Preparatory School and John Milledge Academy, both serving grades K-12. These schools offer alternatives to public education, with programs that emphasize college preparation, character development, and extracurricular involvement.[60][61]

Higher education

[edit]Milledgeville is home to three institutions of higher education. Georgia College & State University is the state’s designated public liberal arts university, offering undergraduate and graduate programs across a wide range of disciplines.[62] Georgia Military College serves as a public military junior college, with both associate and bachelor's degree programs.[63] In addition, Central Georgia Technical College operates a local campus that provides career-focused technical training and adult education programs.[64]

Infrastructure

[edit]Highways include:

Baldwin County operates a demand-response public transportation service.[65]

Baldwin County Regional Airport is a general aviation airport located approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) north of downtown Milledgeville.[66][67]

Notable people

[edit]- Melvin Adams Jr, better known as Fish Scales from the band Nappy Roots

- Andrew J. Allen, concert saxophonist

- Nathan Crawford Barnett, Georgia Secretary of State for more than 30 years

- Ella Barksdale Brown, journalist, educator

- Kevin Brown, professional baseball player

- Javon Bullard, college football player for the University of Georgia

- Tasha Butts, basketball player and coach

- Wally Butts, college football coach

- Earnest Byner, professional football player

- Lisa D. Cook, American economist[68]

- Pete Dexter, novelist, journalist and screenwriter

- George Doles, Confederate Brigadier General

- Henry Derek Elis, vocalist for heavy metal supergroup Act of Defiance

- Tillie K. Fowler, politician

- Joel Godard, television announcer

- Marjorie Taylor Greene, United States Representative

- Willie Greene, professional baseball player

- Floyd Griffin, mayor of Milledgeville, state representative, state senator[69]

- Oliver Hardy, motion picture comedian

- Nick Harper, professional football player

- Charles Holmes Herty, academic, scientist, businessman and first football coach at the University of Georgia

- Leroy Hill, professional football player

- Maurice Hurt, professional football player

- Edwin Francis Jemison, Civil War soldier who died in battle

- Sherrilyn Kenyon, author[70]

- Grace Lumpkin, writer

- William Gibbs McAdoo, US Secretary of the Treasury

- David Brydie Mitchell, the only Governor of Georgia buried in Milledgeville

- Celena Mondie-Milner, professional track and field player

- Powell A. Moore, politician and public servant

- Otis Murphy, international saxophone soloist and professor at Indiana University Jacobs School of Music

- Flannery O'Connor, author, winner of the 1972 U.S. National Book Award for Fiction

- Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, historian

- Barry Reese, writer

- Lucius Sanford, professional football player

- Carrie Bell Sinclair, poet

- Tut Taylor, bluegrass musician

- Ellis Paul Torrance, psychologist

- Larry Turner, professional basketball player

- William Usery Jr., labor union activist and U.S. Secretary of Labor

- Carl Vinson, congressman

- J. T. Wall, professional football player

- Rico Washington, professional baseball player

- Rondell White, professional baseball player

- Robert McAlpin Williamson, Republic of Texas Supreme Court Justice and Texas Ranger

- Arlene Simmons,"America's Nurse" COVID-19 Public Hero

References

[edit]- ^ "Milledgeville City Hall". 2017. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Annual Geographic Information Table". U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Baldwin County, Georgia; Milledgeville city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Milledgeville". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Bonner, James C. (2007). Milledgeville, Georgia's Antebellum Capital. Milledgeville, Georgia: Old Capital Press. ISBN 978-1430307860.

- ^ a b c d Bonner, James C. (2007). Milledgeville, Georgia's antebellum capital. Milledgeville: Old Capital Press. pp. 1–275. ISBN 978-0-8203-0424-3.

- ^ a b c d e Johnston, Lori (March 1, 2015). "Going to Town". Georgia Trend Magazine. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ "Treaty with the Creeks, 1802". Tribal Treaties Database. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clark-Davis, Amy E. (2011). Milledgeville. Images of America. Charleston, S.C: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-8793-6.

- ^ "Georgia Penitentiary at Milledgeville". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c Turner, James C.; Davis, M.; Vacula, Tim, eds. (2013). The old governor's mansion: Georgia's first executive residence (1 ed.). Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-88146-444-3. OCLC 857772887.

- ^ "Oglethorpe University". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ "Acts of the General Assembly of the state of Georgia, passed at Louisville, in December, 1805" (PDF). Digital Library of Georgia. Georgia General Assembly. 1805. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (February 3, 2017). "Confederate States of America established, Feb. 4, 1861". POLITICO. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ Williams, Teresa Crisp; Williams, David. ""The Women Rising": Cotton, Class, and Confederate Georgia's Rioting Women". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 86 (1): 68–72 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Georgia Penitentiary at Milledgeville".

- ^ Carr, Matt (2014). "General Sherman's March to the Sea". History Today. 64 (11): 29–35 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ "Georgia State Capitol". Cit of Atlanta, GA. Retrieved April 17, 2025.

- ^ "History and Vision". Georgia Military College. Retrieved April 18, 2025.

- ^ "Our Heritage & History - About Georgia College". Georgia College & State University. Retrieved April 18, 2025.

- ^ Gisolfi, Monica Richmond. "From Crop Lien to Contract Farming: The Roots of Agribusiness in the American South, 1929-1939". Agricultural History. 80 (2): 170–171 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Thompson, Joanne J.; Martini, Maryann O. (2007). "An Historical Analysis of Institutional Care of the Mentally Ill in the South: Georgia's Central State Hospital". Arete. 31 (1/2): 103–119 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Dwyer, Ellen (2019). "The Final Years of Central State Hospital". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 74 (1): 107–126. ISSN 0022-5045.

- ^ Monroe, Doug (February 18, 2025). "Asylum: Inside Central State Hospital, once the world's largest mental institution". Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved April 19, 2025.

- ^ a b "Our Story". Georgia's Lake Country. Retrieved April 19, 2025.

- ^ "Milledgeville Wins Downtown Development Award". Georgia Public Broadcasting. August 21, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Young, Ben (2004). "Town and Gown in Harmony". Georgia Trend. Retrieved April 20, 2025.

- ^ a b "Central State Hospital". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ "How Geology Shapes History". Retrieved April 21, 2025.

- ^ "Soils". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ reports, Staff (October 18, 2016). "Special ceremony marks opening of Fall Line Freeway". Moultrie Observer. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ "Annual Geographic Information Table". U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2025.

- ^ "Oconee River". Georgia Rivers. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ "JetStream Max: Addition Köppen-Geiger Climate Subdivisions | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration". NOAA. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Milledgeville Climate, Weather By Month, Average Temperature (Georgia, United States) - Weather Spark". Weather Spark. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Snowfall Extremes | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI)". www.ncei.noaa.gov. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Milledgeville, GA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Atlanta". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Georgia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Milledgeville city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (2023). "American Community Survey 5-year estimates". Census Reporter Profile page for Milledgeville, GA. Retrieved April 26, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "About Race". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b Rosen, Karen (October 31, 2013). "Milledgeville | Baldwin County: Ready For Industry". Georgia Trend Magazine. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ Manley, Rodney (January 28, 2009). "Milledgeville plant to close; 150 to lose jobs". The Macon Telegraph. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sargent, Tucker (April 9, 2024). "Ossoff secures $1.1M for industrial park upgrades in Baldwin County". 41NBC News, WMGT-DT. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "'It's really uplifting': Milledgeville shop owners look to future as businesses get national accreditation, funding". WMAZ. June 11, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Community Overview". Development Authority of the City of Milledgeville & Baldwin County. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b Coco, Claudia (December 5, 2018). "Milledgeville says it feels part of $16B impact from Georgia universities, colleges". WGXA. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b "Deal: Tourism industry generates record $60.8 billion economic impact". Visit Milledgeville. February 23, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Visit Milledgeville: Georgia's Ultimate Small-Town Getaway". Explore Georgia. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b "Meet Our City Council". City of Milledgeville. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Milledgeville Code of Ordinances, Article II, Section 7 — Powers of Mayor and Aldermen". Municode Library. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hobbs, Billy (November 7, 2017). "Parham-Copelan upsets Thrower in mayor's race". The Union-Recorder. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Baldwin County School District - Schools". Baldwin County Schools. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Search for Public School Districts - District Detail". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved April 20, 2025.

- ^ "Georgia Military College Prepatory School | About GMC Prep". Georgia Military College Preparatory School. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Academics". John Milledge Academy. January 13, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "About Georgia College". Georgia College & State University. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Discover GMC". Georgia Military College. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "About the Milledgeville Campus". Central Georgia Technical College. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Public Transportation". Baldwin County Georgia. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Getting Here - Air Travel". Visit Milledgeville. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Baldwin County Airport | Airport near Milledgeville GA | United States". Baldwin County Regional Airport. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Women in Economics: Lisa Cook". Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Hobbs, Billy (March 2021). "Milledgeville's first Black state senator, mayor honored". The Union-Recorder. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Staples, Gracie Bonds. "This Life: Author's dark tales an escape from darkness in her own life". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Further reading

[edit]- James C. Bonner, Milledgeville, Georgia's Antebellum Capital, Old Capital Press, Milledgeville, Georgia, 2007. ISBN 978-1430307860. A comprehensive overview of Milledgeville’s history as Georgia’s state capital.

- Amy E. Clark-Davis, Milledgeville, Images of America series, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, S.C., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7385-8793-6. A photographic overview of the city's history.

External links

[edit]- Official Website

- Visit Milledgeville

- Milledgeville Historic Newspapers Archive at Digital Library of Georgia

- Milledgeville, Georgia

- 1804 establishments in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Cities in Baldwin County, Georgia

- Cities in Georgia (U.S. state)

- County seats in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Former state capitals in the United States

- Milledgeville micropolitan area, Georgia

- Planned communities in the United States

- Populated places established in 1804